Help for serious mental health problems

There has been a huge increase in the number of children requiring treatment for serious mental health problems including eating disorders, according to recent NHS data.

The data reveals a reveals a significant rise, 39%, in referrals for NHS mental health treatment for under-18s, to more than a million (1,169,515) for the period 2021/22. This is in comparison to 839,570 referrals in 2020/21 and 850,741 referrals in 2019/20. The referrals include children who are suicidal, self-harming, suffering serious depression or anxiety, and have eating disorders.

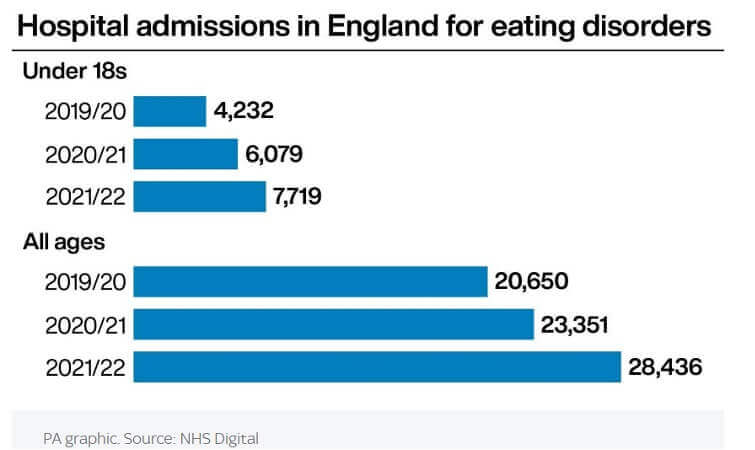

Additionally, NHS Digital data also shows hospital admissions for eating disorders are on an upward trend and rising among children and young people, with 7,719 admissions in 2021/22 among under-18s, up from 6,079 the previous year and 4,232 in 2019/20. This equates to an 82% rise across two years.

The most recent data available, from April to October 2022, reveals there were 3,456 admissions, up 38% from 2,508 for the same period in 2019, before the pandemic.

There were also 3,011 admissions from April to October 2020, as well as 4,600 for the same period in 2021 when the full effects of the pandemic were felt.

The data also suggests that 2022/23 could see the highest number of hospital admissions for people of all ages for eating disorders. From April to October 2022, there were 15,083 admissions, compared with 28,436 for the whole of the previous year (2021/22).

Anorexia, the most prevalent eating disorder, is leading to hospital admissions among all ages with 10,808 admissions in 2021/22. Bulimia is the next most common, with 5,563, while other eating disorders accounted for 12,893 admissions.

Dr Elaine Lockhart, chairwoman of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Faculty at the Royal College of Psychiatrists, said the surge of referrals for children and young people reflects a "whole range" of illnesses. She said specialist services are needed to respond to the "most urgent and the most unwell", including youngsters who have psychosis, suicidal thoughts and severe anxiety disorder. She stated that more staff were needed and that targets for seeing children urgently with eating disorders were sliding "completely".

"I think what's frustrating for us is if we could see them more quickly and intervene, then the difficulties might not become as severe as they do because they've had to wait," Dr Lockhart added.

An NSPCC spokesperson said: "These alarming figures are sadly reflected in the conversations we are having through Childline. The service delivers tens of thousands of counselling sessions every year to children and young people who are self-harming, suffering depression or anxiety, experiencing suicidal thoughts and have eating disorders."

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesman said: "Improving eating disorders services is a key priority and we're investing £53m per year in children and young people's community eating disorder services to increase capacity in 70 community teams across the country."

"We are already investing £2.3bn a year into mental health services, meaning an additional 345,000 children and young people will be able to access support by 2024 - and we're aiming to grow the mental health workforce by 27,000 more staff by this time too."

According to Tasmin Ford, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Exeter, "What is without doubt, is that referrals to CAMHS have skyrocketed and lots more young people are presenting with self-harm to accident and emergency, too. So we are seeing an increase in demand for services but that is not necessarily because more young people are struggling in the community. The data does not support that," she says.

"What I think we are seeing is more people willing to come forwards and saying ‘I need help, I have a problem’. And in the era of austerity followed by the pandemic, other services that were doing mental health work are pulling back. We have a perfect storm of more people seeking help, and less people available to give that help. We have massively underfunded mental health services."

Professor Ford stresses that mental health should not be seen as a bigger problem for secondary schools. While mental health challenges get more common as children get older, many of these challenges begin at earlier ages.

"We actually found 1 in 18 2- to 4-year-olds had difficulties that were significant enough to count as a mental health condition," she reveals.

Supporting Mental health and well-being in schools

So, what does Professor Ford recommend schools actually do to support young people? Her message is that what teachers , which in my opinion should also include pastoral staff, should not be doing is becoming counsellors to fill the void left by support services. She states:

"We need to equip teachers with the means to find out about things from reliable sources, but we do not need to turn teachers into counsellors. What they need is structures in schools that can plug them into the support available."

However, Professor Ford doesn’t advocate moving mental health services into schools but believes a local and context-dependent model is needed. For this approach to be effective there needs to be more understanding around how school structures and actions link with mental health challenges.

"Exclusion from school is very strongly linked to mental health - in both directions." From a 2004 survey (see References), not only were children with a psychiatric disorder more likely to be excluded, but it worked the other way around, if you had just the children doing well, those who were later excluded were more likely to have poor mental health, adjusting for a whole lot of other factors that might have been feeding into that picture.

"I think we should not underestimate the influence of the school, which can be highly positive but also for some children highly negative. It is no doubt very painful for teachers to realise that the structures of the school may not be good for the mental health of pupils."

Overall, she says there has to be more urgency in the system to better support young people when they first seek out support.

"We need to think about this properly: if a child is not functioning at their best between the ages of, say, 11 and 16, just think what that does to your life chances. These are really crucial years. We have effective treatments, but we just don’t have enough people to deliver them."

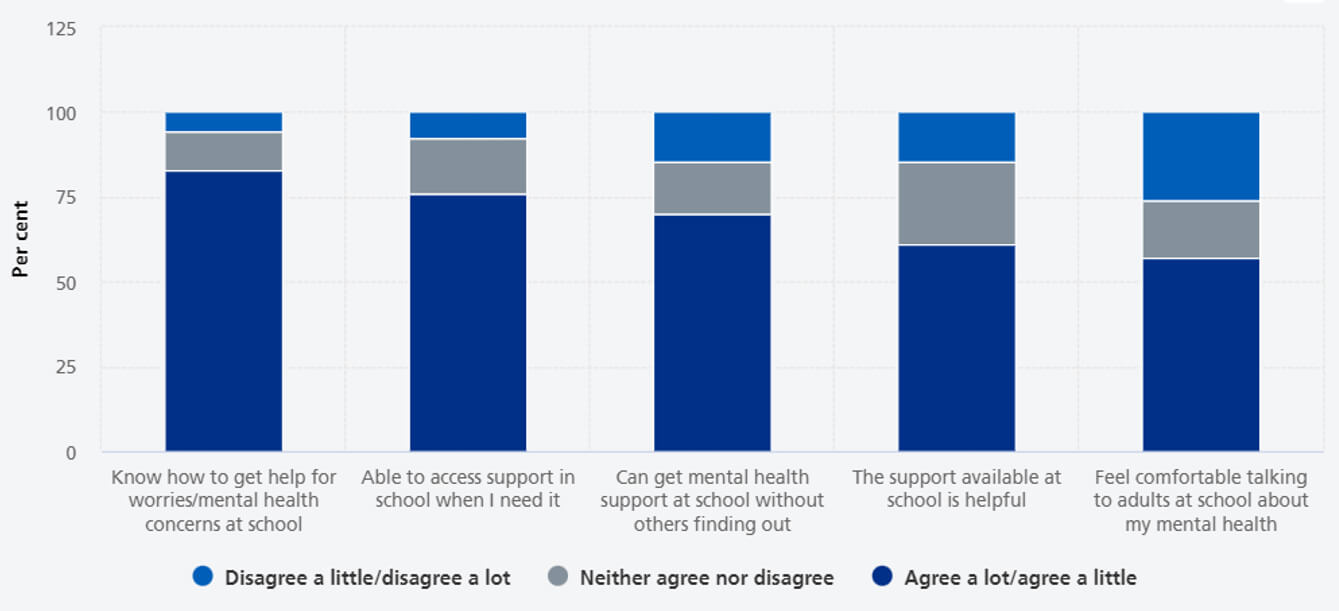

The NHS (2022). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England 2022 - wave 3 follow up to the 2017 (2022), found that the majority of children were positive about access to support at school: 83.0% knew how to get support and 75.9% agreed they were able to access support if they needed to. However, children were less likely to be positive about the value or appropriateness of the support available at school: 61.1% agreed it would be helpful and 57.0% felt they would feel comfortable talking about their mental health with adults at their school.

Training school staff to support mental health is key

So, having staff who are trained and skilled in Mental Health, such mental health first aid and mental health awareness in children, will enable them to recognise the warning signs of mental ill health in young people and help them to develop the skills and confidence to approach and support someone, whilst keeping themselves safe. Training will provide the knowledge to spot specific warning signs that a young person could be struggling with a mental health condition, how to initiate a supportive conversation, explore healthier lifestyle choices and link to additional support available if the young person needed further help.

Check out our ‘Supporting the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Children and Young People’ course.

- NHS Digital. (n.d.). Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004.

- NHS Digital (2018). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017. [online] NHS Digital.

- NHS (2020). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020: Wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey. [online] NHS Digital.

- NHS Digital (2021). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England 2021 - Wave 2 Follow up to the 2017 Survey. [online] NHS Digital.

- NHS (2022). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England 2022 - wave 3 follow up to the 2017 survey. [online] NHS Digital.

Sara Spinks

SSS Author & Former Headteacher

12 January 2023